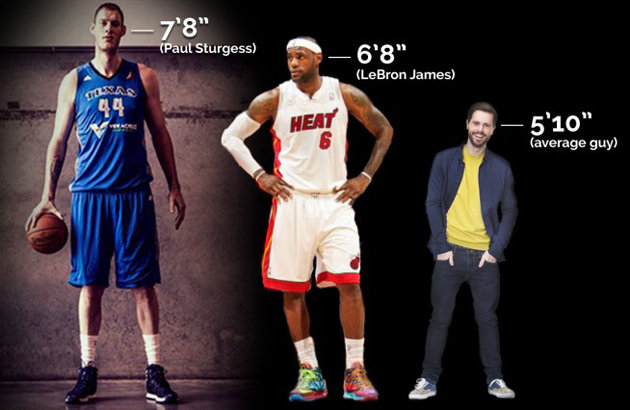

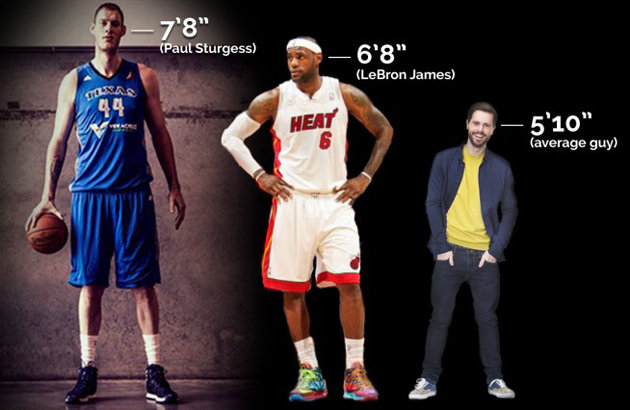

One would think basketball should be easy for Englishman Paul Sturgess. At 7-foot-8, Sturgess, the center for the NBA Development League’s Texas Legends is the tallest professional basketball player in the world. The rim stands less than three feet above his head and is within reach of his long, gangly arms. His opponents, D-League players who would be tall in any other setting, look like jersey-wearing Lilliputians compared to Sturgess. But great height comes with great challenges, and late into the Legends’ season, Sturgess had appeared in just 12 games, averaging only 0.9 points and 0.9 rebounds per outing. He hadn’t yet registered a block.

Sturgess hasn’t seen much court time, because despite his size, his body isn’t yet court-ready in the eyes of many. And as it turns out, developing Sturgess’s body to handle the demands of pro basketball is surprisingly complicated. For starters, Sturgess is not especially well-conditioned. The 26-year-old left his native England in 2007 to play college ball in the States, and after school he joined the Harlem Globetrotters in 2011. There, he was known for his “No Jump Dunk.” He played in exhibition games for a team focused on entertainment, not competitive development. “Not to take anything away from Paul’s accomplishments with the Globetrotters, but they didn’t practice, they rehearsed,” said Travis Blakeley, the Legends’ director of player personnel and assistant coach. “(The Globetrotters) had zero weight room time, zero performance time.”

Blakeley began working with Sturgess after the tall hipster joined the Legends, in November 2013. On Sturgess’s first day of practice, his feet bled through his shoes as he tried to keep up with his team-mates running up and down the court. His size 22 dogs weren’t ready for the speed of the professional game. So Blakely tried a different approach, putting Sturgess through workouts on a stationary bike and light shuttle runs, bouts of cardio that placed less stress on his lower extremities than running the court. “We were taking on an extremely green athlete and had to scale it way back to the basics,” Blakeley added. After weeks of work, and with some new kicks and tape on his feet, Sturgess was in better shape. But he still needed to develop the strength to handle the pounding of the inside game.

Unfortunately, his extreme height, combined with his weight (320 pounds), makes many athlete-development moves like Squats and Lunges risky for him, since they place an undue amount of stress on his knees, hips and lower back. Instead, Blakeley had Sturgess start out with Leg Presses, which develop lower-body strength without subjecting the knees to as much wear and tear. Another issue preventing Sturgess from seeing significant minutes is the league’s verticality rule, which requires referees to call a foul whenever a player does not jump straight up in the air while defending a shot.

Sturgess, like many tall people, tends to slouch. And since he’s been very tall during his entire adult life (he reached the 7-foot mark at age 16), Sturgess has developed a bit of a hunch in his neck, back and shoulders from many years of slouching. This posture makes it almost impossible for him to adhere to the rule, turning what should be his greatest strength (guarding the rim) into a reason for referees to blow the whistle. “Paul struggles just to bring his hands even to a 90-degree plane at his head and shoulders,” Blakeley said. “He tends to be about 6 inches out in front of his head. While that’s still very high up in the air, it’s an easy indicator for the referee to blow his whistle.” To combat this, Blakeley has Sturgess perform Shoulder Presses and Shoulder Flies with very low weight to open up his neck and shoulders. He also uses an on-court drill called “Hot Box,” in which Sturgess stands 3 feet from the rim, back to the basket, and attempts to catch basketballs thrown at his body. The balls can be thrown toward his chest or out to his right or left, forcing him to quickly move his hands and body. After catching the ball, he turns around and puts it through the hoop. “That’s why flexibility in [Paul’s] shoulders and neck is a huge priority for us,” Blakely added. “We need to make it so that when he goes up, he goes straight up without any angle in his arms or in his shoulders to avoid those type of fouls.”

Sturgess struggles the most with what Blakeley calls “dynamic movements” quick bursts of acceleration and sudden changes of direction. A smaller, more mobile player can throw Sturgess off balance. So Blakeley has him working to improve flexibility in his hips and strengthen his inner abs and core, which should help him keep his balance when he reacts to speedy moves. Sturgess also jumps rope and performs agility drills to improve his reaction time. “I’ve been (jumping rope) for a couple months now, and I am already feeling the benefits of how much better I move,” Sturgess said. “It helps me jump quicker and more explosively. I also do a lot of agility exercises and lateral slides, which helps me open up my hips and helps me move.” The work is beginning to pay off, according to both men. Sturgess is making progress in his workouts, and Blakeley is slowly adding strength-building exercises like Squats to the lofty center’s routine.

Blakeley’s goal is for Sturgess to reach the point where he can stay on the court for 12 to 14 consecutive trips up and down the floor at the D-League pace, which is significantly faster than the NBA’s the top four teams average over 110 points per game, including the leading Rio Grande Valley Vipers, who score 123.5 points per game, 16 more than the Los Angeles Clippers, who lead the NBA. Blakeley also wants Sturgess to get to a point where he feels like an integral part of the team. “You know the old song, ‘I wish I was a little bit taller, I wish I was a baller’? It’s a great wish, but at Paul’s size, you wish you were a little bit normal,” Blakeley said. “Of course, there are certain times when he gets frustrated. But he’ll take the frustration and turn it around and work that much harder.” Sturgess has plenty of frustrating days, but he always keeps his mind on the future. He said: “I never compare myself to other people. Whenever I’m doing an exercise, I never think about how well I’m doing now. If I do it every day, I’m going to get better. I always have that in my mind.”

Source: Eurosport.